Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), the newly installed Senate majority leader, is fond of lambasting the Obama administration for its “war on coal’’ and its impact on his Kentucky constituents. Following the latest U.N. climate change meeting in Peru in December, for example, McConnell criticized the administration for its “entire international crusade against coal jobs” and pledged that he would “continue to take the war on coal right back to the president and his EPA with laws aimed at protecting coal jobs….”

Too bad the senator wasn’t so worried about those same jobs prior to President Obama’s election in 2008.

A review of the commonwealth’s own coal mining statistics1 shows that the industry has been in decline for years—driven by nothing more than market forces that punish high cost producers. The same market forces that Republicans tend to champion, at least in the abstract.

For example, the peak year for Kentucky coal production was way back in 1990, when the state mined 179.3 million tons of coal. By the end of 2008 the state’s total output had dropped to 120.4 million tons. And this decline certainly wasn’t due to any “war on coal”: During the same period overall U.S. output rose from 1.03 billion short tons to 1.12 billion short tons, driven largely by a sharp rise in production in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin region.

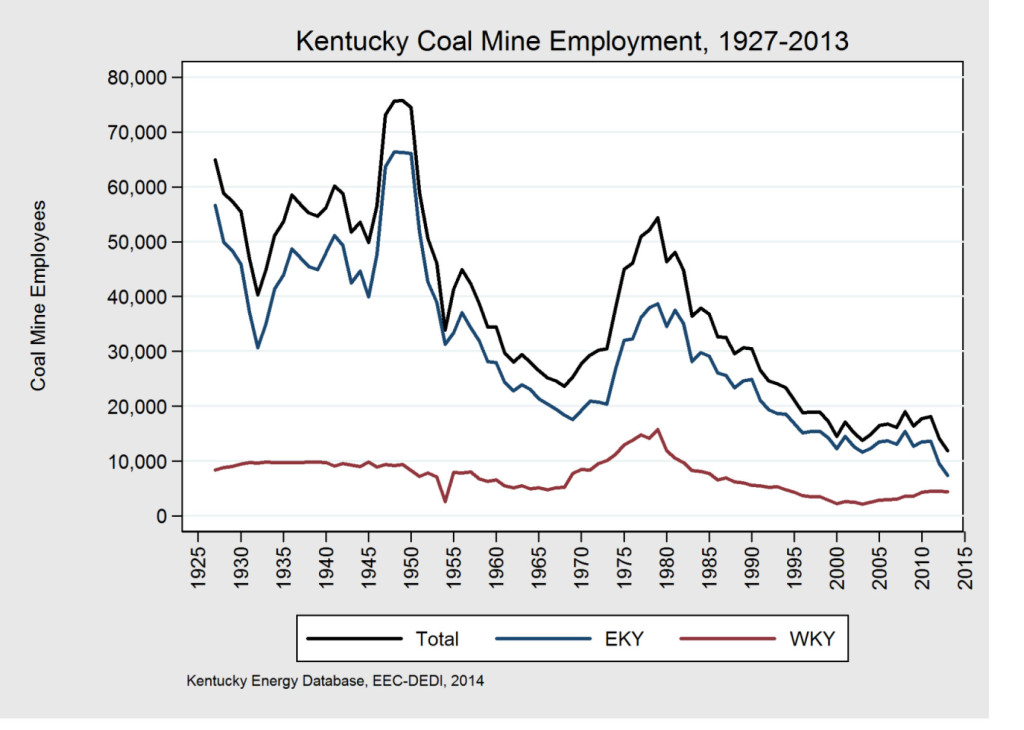

During the same period, the number of mining jobs in Kentucky’s coal industry fell at an even faster rate than the state’s production, dropping from 30,498 to 18,574. Just for reference, the peak year for Kentucky mining employment was 1949, when a total of 75,633 miners worked Kentucky’s fields.

The declines during this period were concentrated in Kentucky’s eastern underground mines, where production fell from 81.5 million tons in 1990 to 45.4 million tons in 2008 and employment dropped from 17,407 to 8,853.

Why? Because eastern Kentucky coal is hard to mine and, consequently, expensive.

Productivity in eastern Kentucky, including both the region’s underground and surface mines, was 2.7 tons per miner per hour in 1990, it rose through the decade to 3.9 tons/miner/hour in 2000, before dropping again to 2.6 tons/miner/hour in 2008. In contrast, productivity in the western U.S., which includes the Powder River Basin region, climbed from 11.8 tons/miner/hour in 1990, to roughly 20 tons/miner/hour throughout the 2000s. Even after you factor in the transportation costs, western coal is simply much cheaper: At the end of 2008, the delivered cost of eastern Kentucky coal was more than $3.50 million British thermal units—two times the delivered cost of PRB coal.

Market forces work, as even the state-produced Kentucky Coal Facts acknowledged in its 2014 edition:

Since the year 2000, however, diminishing reserves of thick and easily accessible coal seams in eastern Kentucky have made coal more difficult, labor-intensive, and costly to mine, which has resulted in reductions in price competiveness of Kentucky coal vis-à-vis coal from other regions and alternative sources of energy. Kentucky coal has been under increased competition from cheaper Powder River Basin coal since the 1980s and from natural gas produced through advances in hydrologic fracturing technology since the 2010s.

That is a paragraph Sen. McConnell and his staff need to read carefully. While it may be painful to admit, the problems facing the Kentucky coal industry cannot be blamed solely, or even primarily, on the Obama administration—they are the result of long-term market forces. Kentucky’s coal resources, while plentiful, can’t compete with cheaper PRB coal, or the gusher of new natural gas reserves coming into play nationwide as the result of widespread hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling.

While only a Democratic pollster would say they were related, the boom in new natural gas supplies largely began in 2008 and has shown no sign of slowing down in the six years since President Obama’s election. Output from the Mid-Atlantic’s Marcellus shale gas region, for example, has risen from essentially nothing in the mid-2000s to more than 15 billion cubic feet per day in 2014. That is roughly 5.5 trillion cubic feet annually—and the Energy Information Administration sees plenty more where that came from. In its 2014 Annual Energy Outlook, EIA projected that shale gas production will account for 53 percent of overall U.S. output by 2040.

That type of new resource—cheap, abundant and clean—changes energy equations across the board, and not in coal’s favor. In just four years, from 2009-2013, natural gas’ share of the electric generation market climbed from 23 percent to 27 percent, while coal’s dropped from 45 percent to 39 percent.

Like the earlier shift from hard-to-mine Eastern coal to easier to reach PRB resources, the switch to newly available natural gas was not due to government fiat, but rather market dynamics.

When you tout the benefits of the market, you have to be willing to accept the market’s decisions.

–Dennis Wamsted

1) The coal statistics cited in this post were drawn from the 11th and 14th editions of Kentucky Coal Facts.

Follow

Follow