Energy Secretary Rick Perry clearly has bought into the fact-challenged approach to governing perfected by President Trump and now practiced almost daily by White House spokesman Sean Spicer: In a speech last week to the National Coal Council, Perry told the group that one of key problems from the Obama administration’s energy policies is “that we’re seeing this decreased diversity in our nation’s electric generation mix.”

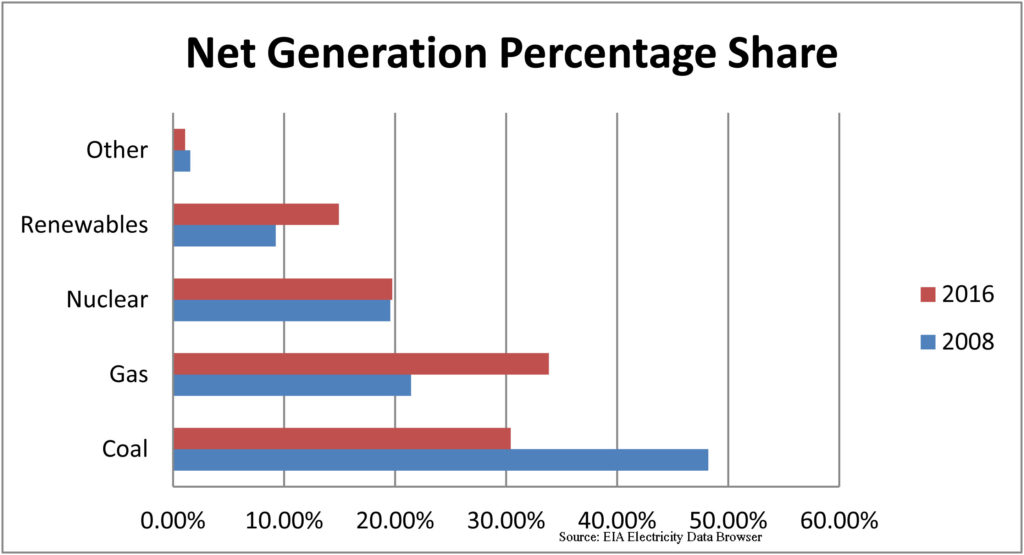

Unfortunately for Perry, the fact is that the nation’s electric generation mix actually is much more diverse today than it was eight years ago. According to data from EIA, the independent statistics arm of his new agency (the same one, of course, that he forgot he wanted to eliminate back in the 2012 presidential campaign), the U.S. grid is demonstrably, provably and irrefutably more diverse now, as the chart below demonstrates.

Coal’s share of the market, as everyone knows, has fallen, dropping from roughly 50 percent of the total in 2008 to just under a third today. In its place, the amount of gas generation has shot up, and now accounts for about a third of the nation’s generation total as well. The rest of coal’s lost market share has been gobbled up by the wind and solar industries, with nuclear largely unchanged. Objectively, a system where two sources account for roughly 33 percent of the total, a third 20 percent and a fourth 15 percent is significantly more diverse than one with a single resource accounting for almost 50 percent of the total, and the next two at roughly 20 percent each.

Secretary Perry may not like the changes, but to say that something is not what it is, indeed, to say that it is the opposite of what it is, borders on the irresponsible. Worse, the secretary is using this and a number of other questionable assumptions as the basis for a department study looking into issues surrounding the “long-term reliability of the electric grid.”

Given the tight time-frame, supposedly just 60 days, the study (the memo can be found here) won’t include much, if any new research or modeling; the timing simply won’t allow it. In fact, given the tone and tenor of the secretary’s letter calling for the study, the report largely could be written today: Coal is good, change is bad and the Obama administration is to blame for the mess in which we now find ourselves.

That may be a bit of a reach, but consider this third point in Secretary Perry’s memo, which directs the department to examine “the extent to which continued regulatory burdens, as well as mandates and tax and subsidy policies, are responsible for forcing the premature retirement of baseload power plants.”

But don’t worry about market forces, such as those unleashed by the surge in natural gas supplies during the past decade. Just this week, for instance, EIA put out some new data about U.S. natural gas production showing that Pennsylvania and Ohio now account for 24 percent of annual domestic output—up from less than 2 percent in 2006. That kind of growth can change everything, and it has.

As I have written before (see here), many of the coal plants retired over the past several years have been older, smaller and less efficient. Specifically, in early 2016 EIA looked at the 94 coal-fired plants retired in 2015 and reported that on average they were older, 54 compared to 38 for the plants still in operation, and smaller, with an average net summer capacity of 133 MW compared to 278 MW for the remaining coal fleet.

More important, at least in my book, is that the capacity factor of the retired plants trailed that of the fleet as a whole by a wide margin. EIA said the average coal plant in 2015 posted a capacity factor of 55 percent; not so far the retired 94. During 2013 and 2014 (I opted to omit the 2015 data since the capacity factors for the retired/retiring places obviously would be negatively affected that year), the class of 2015’s 94 plants posted an average capacity factor of 26 percent (2013) and 28.6 percent (2014)—well below the fleet average those two years of 60 percent and 61 percent, respectively.

In other words, there was noting “premature” about the closure of these plants–they were simply waiting to be retired.

And even when you look at the larger plants that posted above average capacity factors, it is hard to escape the power of the market. Here, FirstEnergy’s three unit, 1,710 MW Hatfield’s Ferry plant in southwestern Pennsylvania is a great example. The three units were shut down in October 2013 even though the plant posted an average capacity factor of 70.5 percent in the three years (2009-2012) immediately prior to the closing. Clearly, saying the units were running well would be an understatement. Still, FirstEnergy opted to close them, and to do so quickly. The closure was announced July 9, 2013, and the plant was taken off line on October 9—the 90-day interval required by PJM to give the transmission operator sufficient time to study any potential reliability impacts (it found none).

At the time, much was made of the looming April, 2015 deadline to comply with the EPA mercury and air toxics rule, including FirstEnergy executives who talked extensively about the cost of past environmental rules and the uncertainty of future ones. FirstEnergy estimated in 2013 that it would cost $270 million to bring the Hatfield units into compliance with MATS. But when you dig a little deeper it turns out that even running at 70 percent capacity, and not factoring in the MATS compliance costs, the Hatfield units were in the red.

James Lash, president of FirstEnergy Generation, told a Pennsylvania House of Commons field hearing in October 2013 that the company would have closed down the three-unit facility even without the MATS requirement. “That is correct,’’ he told a questioner at the hearing. “They’re losing money today without spending the money…required to be compliant with MATS…. That just makes it worse.”

The prices available in the PJM auctions—both for energy and capacity—“no longer add up to the cost it takes to run these facilities,” Lash added. “They’re quite a bit less.”

Interestingly, just this month, FirstEnergy announced that it had signed a deal with APV Renaissance Partners to sell a 33 acre-parcel of the Hatfield’s Ferry station and some of the remaining equipment to the Bernardsville, N.J.-based developer, which is planning to build a new 1,000 MW combined cycle natural gas facility at the site—clearly somebody thinks they can make money in PJM.

“The existing infrastructure available at Hatfield’s Ferry and abundant fuel supply in the region make this an ideal location for the construction of a natural gas power plant,” John Seker, president of APV, said when the deal was announced.

Similar change can be seen in Florida, where FPL bought and then closed the 250 MW Cedar Bay coal-fired generating station at the end of 2016. The utility had a long-term power purchase agreement with the facility, originally signed in 1988 and due to run through 2024 that was costing the company $120 million a year, with annual increases through the end of the contract. While the agreement made sense in 1988, FPL said it was uneconomic today because the company “generates far cleaner energy today at a much lower cost.” All told, the utility said the purchase and shut down would save customers roughly $70 million.

“Buying and shutting down old, inefficient coal plants is unprecedented in America,” said Eric Silagy, president and CEO of FPL. “I’m very proud of our employees for proposing this innovative approach that’s environmentally beneficial and saves customers millions of dollars.”

The utility is now working to do the same thing with the Indiantown coal plant. FPL signed a similar PPA with the facility in 1991 but last year received approval from Florida regulators to buy out the plant and shut it down, saving customers an estimated $129 million. As with Cedar Bay, FPL said the Indiantown agreement made economic sense when it was signed in 1991, but times have changed.

Boy have they ever, and that is a point that Secretary Perry and his DOE analysts need to remember. This isn’t the grid or the power generation sector of 10-20 years ago. Times have changed.

–Dennis Wamsted

Follow

Follow

“…on average they were older, 54 compared to 38 for the plants still in operation…”

Did you mean 54 years compared to 38 years?

Maybe that is obvious, am I am just a technical editor at heart.