Last week’s headlines focused on Georgia Power’s newly signed agreement with Toshiba committing (recommitting?) the Japanese parent of bankrupt Westinghouse to pony up $3.68 billion to fund the completion of the long-delayed Vogtle 3 & 4 nuclear power plants. While that is clearly good news (at least for the moment) for Georgia ratepayers, who could otherwise have been stuck with the bill, it has obscured the real news—that no one knows how much it is going to cost or how long it is going to take to complete the two reactors.

The day before Georgia Power’s headline stealing news, staff and the independent construction monitor filed testimony at the Georgia Public Service Commission covering the latest six months of activity at the site (from July 2016-December 2016, with rollover analysis through April 2017). Their conclusion? The project has been a mess since the beginning, and there are still no signs of improvement (although admittedly couched in far more diplomatic/technical language, to which we now turn).

At the macro level, much of the problem can be traced to the absence of a credible integrated project schedule or IPS, an absolute must in a project as complex as this, William Jacobs, Jr., and Steven Roetger told the commission. Jacobs has served as the project’s independent construction monitor since 2009; Roetger is the commission’s lead analyst for the project. They have been highly critical of the Southern/Westinghouse work at Vogtle for years and have warned consistently that the stated completion dates bore no relationship to reality; see my stories here and here.

There have been numerous IPS iterations at Vogtle, Jacobs and Roetger pointed out. The most recent baseline document dates from April 2016, but it shares a common trait with earlier versions–it falls short, way short, of being useful. For starters, the two wrote, “Staff believes not all activities were loaded into the baseline IPS. Or if all activities were loaded, they were loaded with insufficient detail and fidelity to be useful.” To that point, the two noted that the number of activities in the working IPS increased almost monthly from April 2016 through March 2017. The exact number is redacted, because, well actually I’m not sure why but it certainly doesn’t give one the sense that anyone is being truthful about the project schedule.

The garbage in, garbage out approach to the Vogtle IPS has only really accomplished one thing, the two continued: It has delayed the day of reckoning about how long and how much it will cost to complete the two reactors. Perhaps that was the plan to begin with, it’s hard to say.

What Roetger and Jacobs do say is damming enough: “If the parties to the EPC agreement [that would be Southern and Westinghouse] had developed a reasonable, integrated and resources loaded IPS and ETC [estimate to complete], this current expansion of costs to complete the project would have been known, or should have been known, years ago.

“Conceptually, had the company developed a reasonable, fully integrated and resources loaded IPS when staff stated it was necessary beginning the 6th VCM [that would be 2012 for those not tracking this closely] it would have shown that the then current forecast to complete the project (schedule and cost) were severely underestimated.” [Emphasis added]

Supposedly, the two continued, a level 3 IPS will be issued soon. Whether it will be any more accurate than past documents remains to be seen.

Turning to the micro level, the two underscore a host of issues that significantly slowed construction during the past year—and will remain as issues regardless of who picks up the pieces from Westinghouse. Their report focuses on four areas at Unit 3 that are on what they call the “critical path” to the plant’s’ completion and the beginning of fuel loading: the containment building, the shield building, the auxiliary building and the annex building.

Looking at the containment building, the two said the current milestone is reaching an elevation of 107 feet for the concrete inside the structure, which then would allow other work to proceed. While the dates are redacted, the two note that in just a year (April 2016-April 2017) the schedule for completion of this activity has slipped by 272 days.

Concrete issues have plagued the next area as well. The current goal for the shield building is reaching an elevation of 149 feet on its east side (above that level the building will consist of panels). Reaching this height will require 19 separate concrete placements, plus installation of the associated rebar, embeds and wall penetrations. It apparently hasn’t gone well. Again, while the scheduled dates are redacted, Jacobs and Roetger note that the total delay in this work in the past year has now risen to 293 days.

Work on the third area, the auxiliary building, has fared even worse. The goal here is to get the walls and floors to an elevation of 100 feet (which is ground level at Vogtle) so work can continue on the shield building above 149 feet; this is necessary to prevent “differential settling between the two buildings.” Here, they said, the cumulative delay for the past year now totals 340 days.

Finally, there is the annex building, which will house the electrical switchgear that provides power to the plant’s equipment. It must be completed before any startup testing can begin, but that won’t be anytime soon, according to Jacobs and Roetger. Since April 2016, the schedule for completion of the building has slipped 396 days.

The two also caution against assuming that simply changing contractors is going to solve the project’s myriad problems. Fluor took over last year from Stone & Webster and developed a plan that it said would result in a “step change” in productivity within 90 days and raise the monthly construction completion average to 2.3 percent by the end of 2016. It didn’t happen. As the two analysts point out, “overall project performance as measured by monthly percent complete and productivity did not improve during the 16th VCM period. Construction completion per month averaged 1.07 percent per month. …total project completion averaged 0.7 percent per month with a range from 0.5 percent complete per month to 1.1 percent complete per month. These per month percent completions were marginally better than those achieved during the 15th VCM period but certainly not the 2.3 percent per month forecast by the end of the 16th VCM period and only one-third of the 3 percent per month forecast for mid-2017.”

Westinghouse/Fluor also developed what they dubbed a construction performance improvement plan, which was rolled out in August 2016 and revised in October, designed to improve performance at the site. Here too, the results were lacking: “However, these initiatives again had little effect on productivity or production during and after the 16th VCM period,” Jacobs and Roetger wrote.

Low productivity has been “a continuing issue” at the site, they continued, and work throughout 2016 and into 2017 has only resulted in modest improvements. “A second visit by the productivity consultant in February and March 2017 showed some improvement, but indicated that idle time, early quits and late starts remained high,” the analysts wrote.

Turning to Westinghouse’s decision to buy out the former lead construction contractor, Stone and Webster, the two make the point that this was little more than change for change’s sake. “Stone and Webster, regardless of its parent company, was incurring billions of dollars in losses related to the project,” they wrote. “There was no reason to believe that these losses would simply stop because of Westinghouse’s purchase of Stone and Webster.”

In other words, changing contractors isn’t a panacea; there are still major issues in scheduling and work flow that need to be resolved, regardless of who is running the show. That is a point Southern and its leadership should take to heart.

While these delays have been adding up, the project’s economics have been deteriorating, as explained by Philip Hayet and Lane Kollen, consultants with Kennedy and Associates who have testified on behalf of the PSC’s public interest advocacy staff in past Vogtle construction monitoring proceedings. For starters, the two point out that the company and the PSC essentially are back at square one in evaluating the economics of the plant. Westinghouse’s bankruptcy, the rejection of the formerly fixed priced construction contract and the recognition that more delays are on the horizon have invalidated past cost projections and call for a reevaluation, they said.

Even with the ratepayer protections included in the stipulation agreed to by Georgia Power and approved by the PSC earlier this year, the two wrote, “the project may not be economic to complete depending on the revised schedule and costs to complete.”

I would argue that there is no doubt about the economics—they no longer work in Vogtle’s favor, if indeed they ever did. The information Hayet and Kollen present beginning on page 11 of their testimony certainly would be enough to keep me up at night if I worked at Georgia Power. For starters, they point out that the utility’s analysis uses June 30, 2019 and June 30, 2020 as the projected startup dates for the two reactors (this is already a 39 month delay from the assumed original completion dates and is now considered the “base case” by the company). The problem here, they write, is that Georgia Power “now states that the base case in-service dates are not achievable and will be further delayed.”

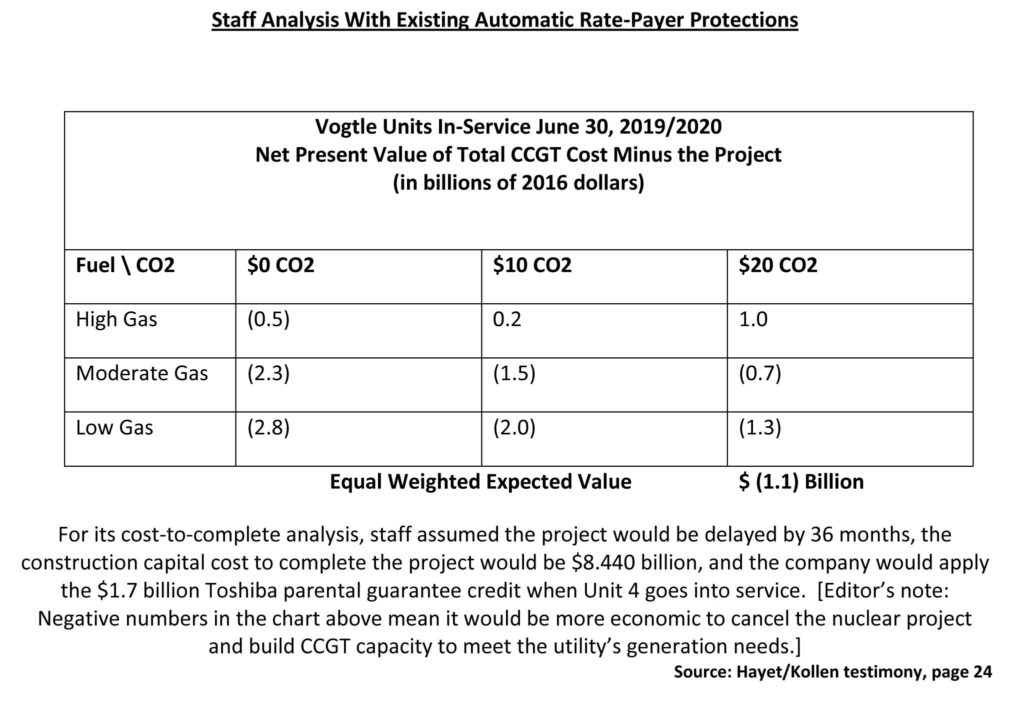

Even using that optimistic scenario, it would cost $1.1 billion more to complete the plant in today’s low gas price/no carbon tax environment than it would to cancel it and build new combined cycle gas turbines.

When you turn to more realistic completion timetables and the additional costs that are likely as a result, the economic outlook for Vogtle is even worse.

In a hypothetical analysis, the commission staff looked at a delay of another 36 months, which would bring the plants online in June 2022 and 2023, and $3 billion more in capital costs, putting Georgia Power’s share at $8.44 billion. Using these parameters, Vogtle is an economic loser (see chart below). Another analysis, taking away the ratepayer protections included in this year’s Georgia Power-PSC settlement, puts Vogtle even deeper into the red.

“Based on these assumptions, it appears that it would be uneconomic for the project to be continued,” Hayet and Kollen concluded.

It is never easy to change course, but simply throwing good money after bad isn’t the answer. It is time for some real soul-searching at the Georgia PSC, which has the ultimate say on whether the plants are finished.

–Dennis Wamsted

Follow

Follow

2 thoughts on “New Analysis

Begs The Question:

Is Vogtle Project

Too Costly To Complete?”