“Facts are stubborn things.”

John Adams, our second president, generally gets credit for this wonderful aphorism, but regardless of who was the first to say it, the observation itself is what matters: You simply cannot wish away facts. This came to mind earlier this week when I looked at the Energy Information Administration’s monthly electric power overview (which can be found here); it’s a publication that only the geekiest of energy wonks would ever read, particularly on a regular basis. However, dry as it may be, it does one thing exceedingly well: It presents facts, just as they are—not as people may want them to be.

One of the many such facts that caught my eye this month concerns electricity generation from coal, that shiny black rock that seems to be the moving force behind all the Trump administration’s energy and environmental policies. ‘The war on coal is over,’ his minions mouth repeatedly. ‘We are going to bring the jobs back,’ the president assures miners at every opportunity.

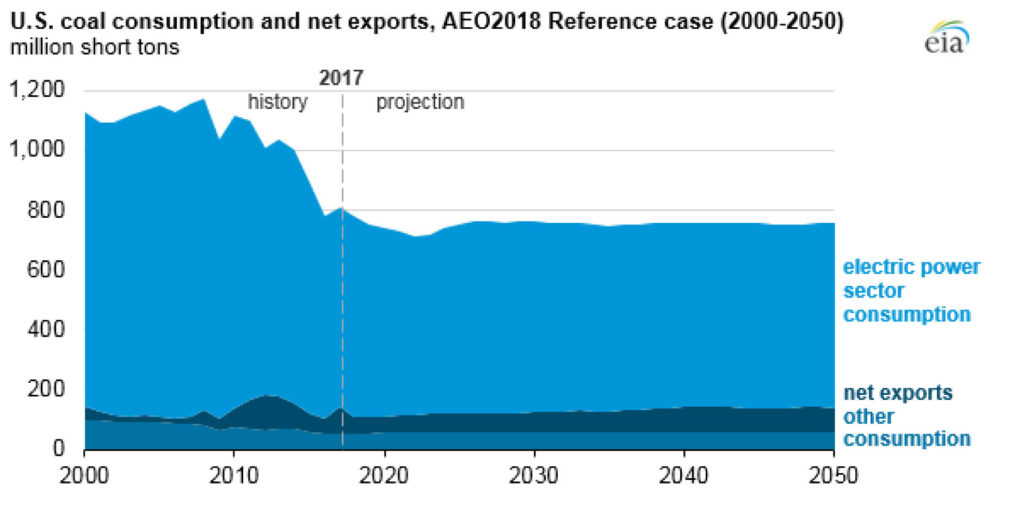

Problem is, facts are stubborn things. In the EIA review, which covers the first nine months of 2017, coal-fired electricity generation fell compared to the comparable year-earlier period. To be fair, it didn’t drop by much, sliding 1.5 percent to 919,805 thousand megawatt-hours from 934,267 thousand mwh a year ago. However, if the war is over and the jobs are coming back, then there should have been no slide at all; indeed, there should have been an increase.

The slide in coal-fired generation also pushed coal production for the sector, which accounts for the vast majority of U.S. coal consumption, down during the first nine months. Overall, just over 504 million tons of coal were used to generate electricity, down from 509 million in 2016—which was the lowest production year for the industry since 1979. Hardly the turnaround the Trump administration repeatedly trumpets.

What the administration definitely doesn’t trumpet in its incessant tweets and coal-dominated decision-making, is that during this same nine-month period, generation from non-emitting wind and solar jumped 13.6 percent, climbing to 284,584 mwh from 250,482 mwh in 2016. Combined with hydro, renewables generated just over 525,000 mwh of electricity annually for the first nine months of the year, within hailing distance of the nation’s nuclear sector, which has generated just under 600,000 mwh so far this year.

And while the administration clearly is not a fan of renewables, more growth in this sector is just around the corner. The American Wind Energy Association says 84,000 MW of wind capacity are installed across the United States, with another 25,000 MW under construction. Similarly, the Solar Energy Industries Association reports that 47,000 MW of solar capacity has been installed in the U.S., with another 21,000 MW of utility-scale solar generation currently in the construction pipeline.

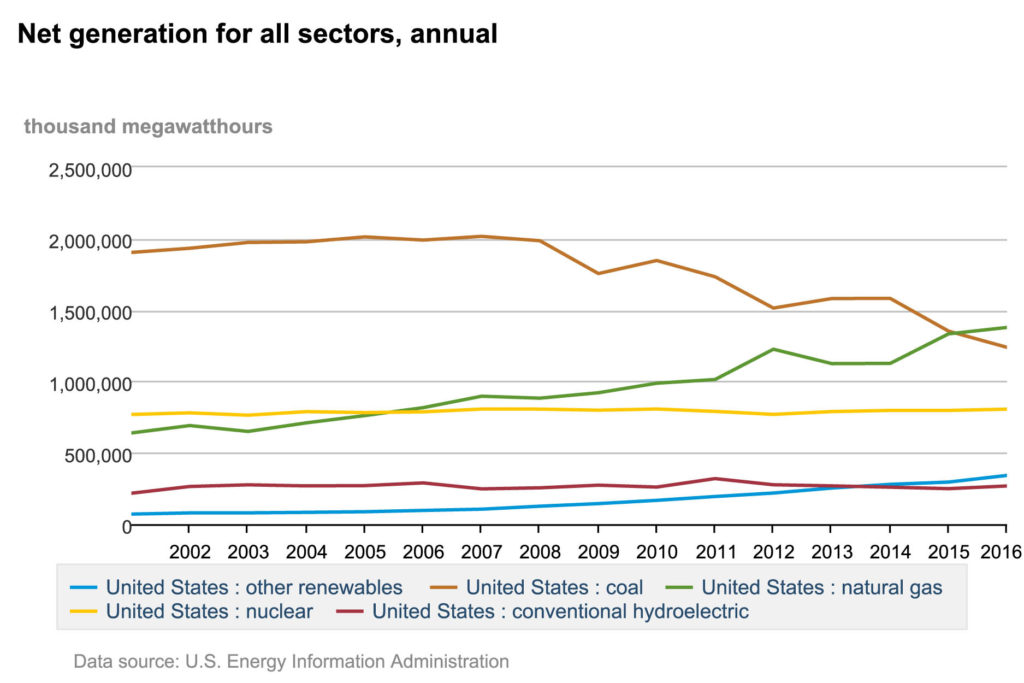

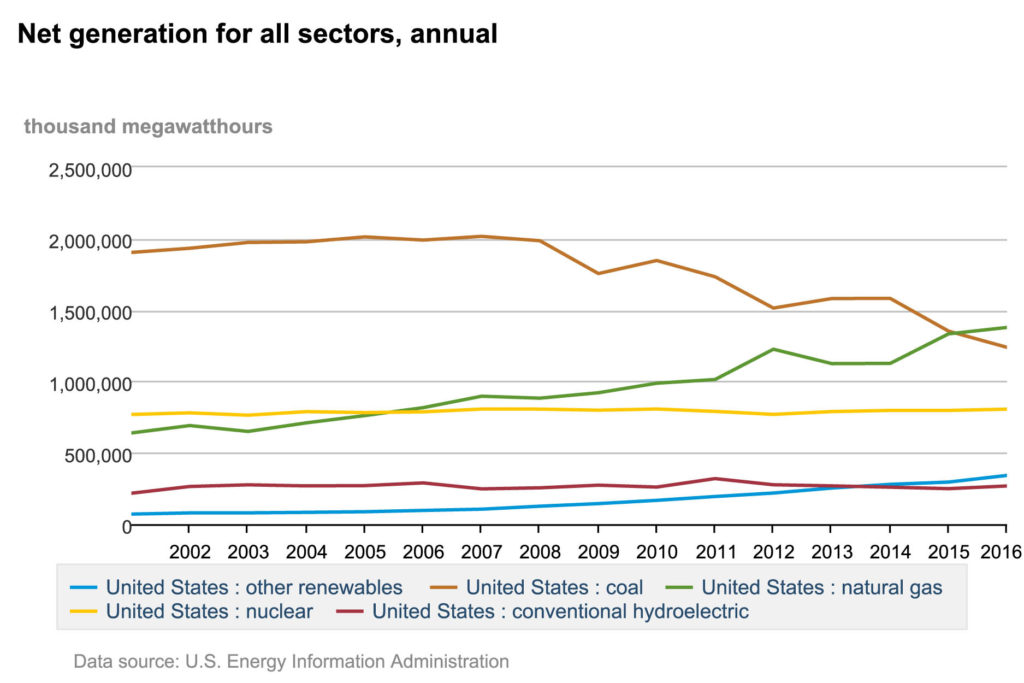

As much as Trump and his backers like to blame renewables and the environmental community for the downfall of coal, the stubborn little fact is that the war, such as it was, against coal was waged, and won, by natural gas. From an expensive afterthought used largely just as a peaking resource during periods of high demand in the early 2000s, natural gas has taken ever-larger chunks of the electric generation market since then. From less than 20 percent of the total in 2001 (when coal’s share was roughly 50 percent), natural gas’ share of the market has climbed steadily, reaching 34 percent in 2016 and topping coal as the largest single source of electricity in the United States (see graphic below).

This transition, in turn, was due to another simple, stubborn fact: Huge quantities of formerly uneconomic gas supplies in the Mid-Atlantic and surrounding regions became accessible at affordable prices due to the commercialization of horizontal drilling and fracking technologies. As EIA noted earlier this year in one of its Today in Energy news stories (available here): “The increase in natural gas generation since 2005 is primarily a result of the continued cost-competitiveness of natural gas relative to coal.”

No war, no hidden agendas, just stubborn economic facts—obvious for anyone to see, provided, that is, they are willing to look.

–Dennis Wamsted

Follow

Follow