It’s been a bad week for the U.S. coal industry. On Monday, Michigan-based Consumers Energy announced that it planned to close all its remaining coal-fired generation by 2040; the company already had closed seven of its 12 coal plants in 2016. Then, on Tuesday, Vectren, an electric and gas utility serving parts of Indiana and Ohio, said it planned to retire three of its coal-fired plants and sell its ownership stake in a fourth by 2023; this from a company that just two years ago was dependent on coal for 90 percent of its generation.

But this week is hardly unique. Just last Friday, FirstEnergy said it was going to close or sell the 1,300 megawatt coal-fired Pleasants plant in West Virginia by Jan. 1, 2019 after being unable to convince federal regulators to approve a deal between two of the Akron, Ohio-based holding company’s subsidiaries that effectively would have moved the facility from the open market into rate base, forcing consumers to pay for the plant even if it was no longer economic.

Not to be forgotten, earlier this month, AEP announced plans to slash its carbon dioxide emissions 60 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050 (based on a 2000 baseline, see my story here). And finally, on Jan. 30, PPL announced plans to reduce its CO2 emissions by 70 percent by 2050 (based on a 2010 baseline).

So, in reality, it’s been a bad month, and similar months are likely moving forward.

FirstEnergy is an outlier in these announcements, but the other four companies all linked their decisions to concerns about climate change—illustrating that while the Trump administration may still want to deny the facts, the utility industry has gotten the message. Change is needed.

Patti Pope, president and CEO of both Consumers Energy and its parent CMS Energy, said the utility’s rationale for cutting its coal use was simple: protect the planet. “We believe it is incredibly important that we step up to the plate and take the appropriate actions to be on the right side of history on a critical issue like climate change,” she said according to MLive.com.

Similar sentiments were voiced by executives at AEP, PPL and Vectren. For example, William Spence, chairman, president and CEO of PPL Corporation said that “as the world considers climate change…[PPL]…will continue to take steps to minimize our impact on the environment, transform the way we generate electricity and incorporate new, lower-emitting technology.” Likewise, Nicholas Akins, AEP chairman, president and CEO, said the goal of the company’s emissions reduction plan was twofold: to provide cleaner energy for customers while protecting investors from climate-related risks. “This long-term strategy,” Akins said, “allows us to do both.” Finally, Vectren pointed out that its plan would cut its carbon emissions by 60 percent by 2024, helping to meet the growing demand from its customers for cleaner energy.

It is unlikely that these will be the last such utility announcements. Or to put it bluntly: The bad weeks for coal are not likely to end anytime soon.

Which brings me to a related issue: the troubling lack of reality concerning coal in the Energy Information Administration’s recently published Annual Energy Outlook. I have frequently relied on EIA figures in past posts and I am generally a big fan of its data collection and interpretation work since it is not tied to any side of the debate. While you can quibble with their numbers, at least you don’t have to worry that they are skewed because of who was footing the bill. However, its coal outlook in the 2018 AEO (which is available here) has me puzzled.

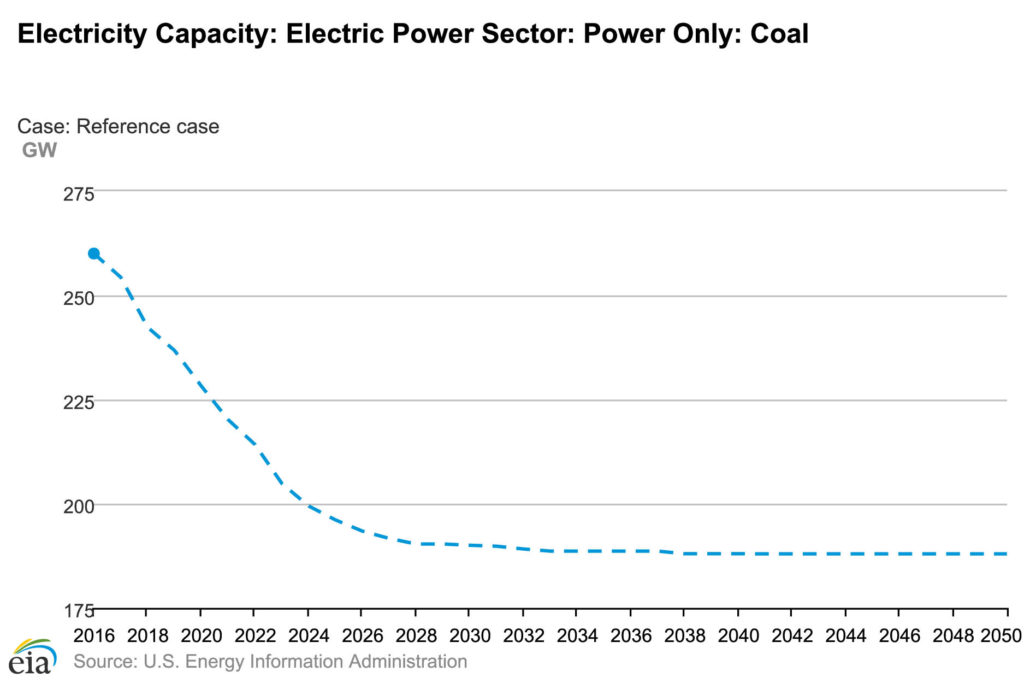

My concern stems from the graphic below, which depicts the reference case in the latest outlook and was downloaded from EIA’s data browser. Not surprisingly, the amount of installed coal-fired capacity is projected to fall sharply over the next five to six years, dropping from about 250 gigawatts now to less than 200 GW around 2024. But then something magical happens—nothing. In its forecast, EIA projects that beginning around 2026 the amount of coal-fired capacity in the U.S. will remain essentially unchanged through the end of its forecast in 2050.

This is tough to swallow for two reasons. First, it is unlikely the bad weeks suffered by coal as outlined above are simply going to end come 2026. Clearly, it would be foolhardy for EIA to try and project future utility generation decisions, but to assume no additional closures also strains credulity.

The bigger issue, though, is that this projection overlooks the fact that by 2050 the nation’s coal fleet will have tottered into decrepitude. In a Today in Energy post last year, EIA pointed out that fully 88 percent of the nation’s coal-fired generation was built before 1990—meaning that even the youngest of the bunch already are 28 years old. More telling, on a capacity-weighted basis, EIA reported, the average age of the coal fleet was 39 years. Add another 33 years and you can see the problem: EIA’s assumption that few, if any additional coal plants will retire after 2026 doesn’t pass the reality test.

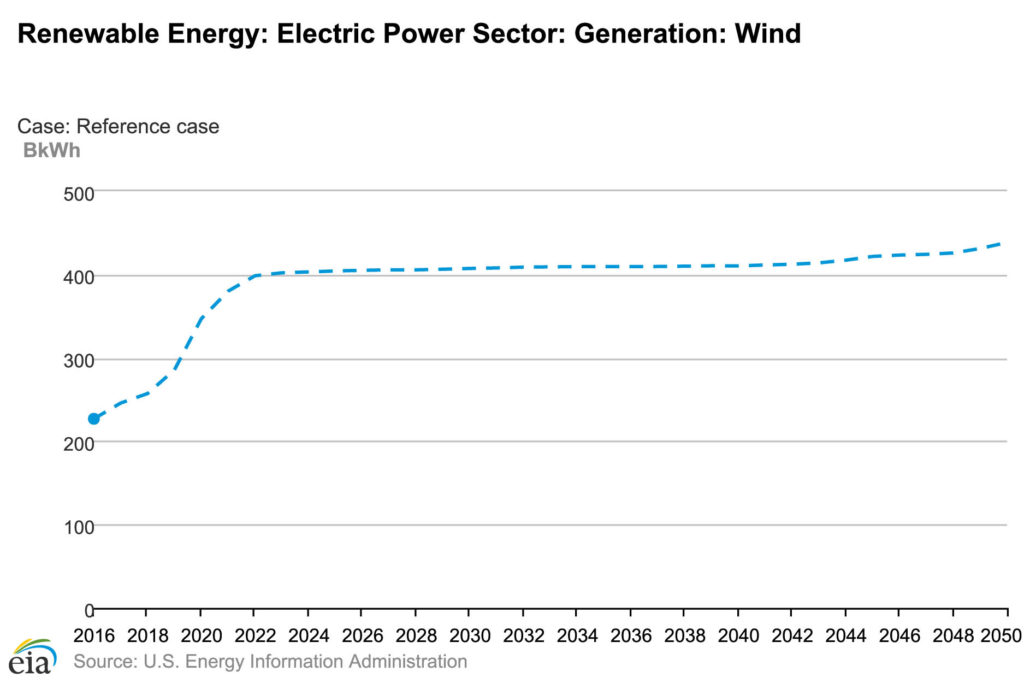

A similar head-scratcher, and one probably linked to its coal plant assumptions, is apparent in EIA’s projection for windpower in the out-years of its annual outlook. That chart (below) shows a sharp increase in new wind generation through about 2022 (roughly coinciding with the scheduled phase-out of the production tax credit—and then, just like the coal sector, wind is expected to flat line through 2040. With the continuing declines in wind generation’s cost, rising corporate and utility interest in renewable energy resources, and the uptick in offshore wind planning, it is unlikely, to say the least, that no new wind generation will be brought on line in the U.S. for a 20-year period.

I am not an energy model expert, but the flat projections in the out-years for both coal and wind are bothersome since both are so unlikely. If EIA wants policymakers and industry observers to take their forecasts seriously, it is going to have to resolve these concerns.

–Dennis Wamsted

Follow

Follow

EIA data about the *past* is good.

But EIA models of the *future* are universally horrible — they are a world laughingstock. Greenpeace has a much better track record at predicting future energy trends!